Forough Farrokhzad

Tehran - TARNA: Forough Farrokhzad Without a doubt, she is among the most famous contemporary poets and the most renowned female poet in Iran. Her poetry began with a bold and feminine tone and quickly became a topic of discussion in society, but gradually matured into its unique voice, making Forough one of the influential poets of the contemporary era. Throughout her life in our society, Forough Farrokhzad faced censorship and public skepticism; it seems our traditional culture could not accept an enlightened and independent woman who dedicated her life to poetry and freedom. Since her untimely death, various materials about her life and poetry have been written and examined from different perspectives. In the forthcoming article, which is prepared in two parts, we take another look at the brief yet eventful life of this valuable poet.

Part

one, Childhood to a new birth

Childhood

and Adolescence

Forough

Farrokhzad was born on December 29, 1934, in the Amiriyeh neighborhood of

Tehran to a father from Tafresh and a mother of Kashani descent. She was the

fourth child of the family. Her father, Colonel Mohammad Farrokhzad, was a

strict military man. Forough says about her childhood: "From childhood, my

father accustomed us to what is called hardship. We slept in military blankets

and grew up, although there were also fine and soft blankets in our house. He

raised us with a specific method he had adopted in his parenting."

The

dictatorial and patriarchal regime that dominated their lives later led to

Forough's rebellion and defiance, as we have often heard described in her

personality as tradition-breaking, rebellious, and norm-defiant. As Forough

herself writes in one place: "Perhaps my father is not pleased to have an

impudent and self-willed daughter like me." Or in a letter she writes to

her father: "Father! Since I came to know myself, my rebellion and

defiance against life also began, I wanted and still want to be great."

-

Forough's childhood alongside her family

In a letter she sent from Munich to her father, she writes that if she were to express all her thoughts to him, it would become a book, but she fears he might be affected. "...My great pain is that you never knew me. And you never wanted to know me... I remember when I was reading philosophical books at home... You used to think I was a foolish girl whose mind had been corrupted by reading nonsense magazines, then I would crumble inside myself, and the tears would gather in my eyes from being so alienated at home, and I tried to choke... or a thousand other similar things, which might not be significant in themselves but are each enough to crush a person's spirit and individuality."

He

writes that his father could have guided his children with kindness, but instead,

he frightened them with his violence: "Often, my soul would tremble with

regret and remorse after making a mistake, and I wanted to come to you and tell

you what I had done, and ask you to advise me, but as always, I was scared and

felt estranged from you."

From

the beginning of her adolescence, Forugh had a great interest and talent in

poetry and writing. Her father would read poetry, and she listened with

interest to familiarize herself with literature. Forugh's talent in her teenage

years was such that her essay teacher couldn't believe she had written her

essays herself.

She

describes her adolescence: "When I was thirteen or fourteen years old, I

used to write a lot of ghazals and never published them... Sometimes, poetry

just naturally flowed from me. Two or three a day, in the kitchen, behind the

sewing machine, I just said them. I was very rebellious. I just kept saying

them. Because it was like a madness that I read behind the madness and was

filled, and after all, I had the talent, so I had to give back somehow."

Youth,

Poetry, Marriage, and Separation

Forugh

Farrokhzad fell in love with Parviz Shapour at the age of sixteen. Parviz was a

writer and journalist known for creating cariclatures, short writings (often

one-liners) with a poetic and humorous view. Besides cariclatures, Shapour was

also skilled in charcoal drawing.

Forugh's

mother and Parviz Shapour's mother were cousins, and Shapour often came to

Forugh's house with his mother, telling stories to her and her younger brother.

Shapour's calm, sensible, well-dressed, and humorous demeanor was attractive to

a teenage girl like Forugh, who lived in a strict and formal family. However,

from the beginning, everyone opposed the relationship due to the significant

age difference between Shapour and Forugh. As a result, the two turned to

letter writing, with Shapour using the pseudonym "Javad Shariaty"

(chosen by Forugh), exchanging letters through Cyrus Bahman (husband of Pouran,

Forugh's sister) and sometimes through Faridoun (Forugh's brother).

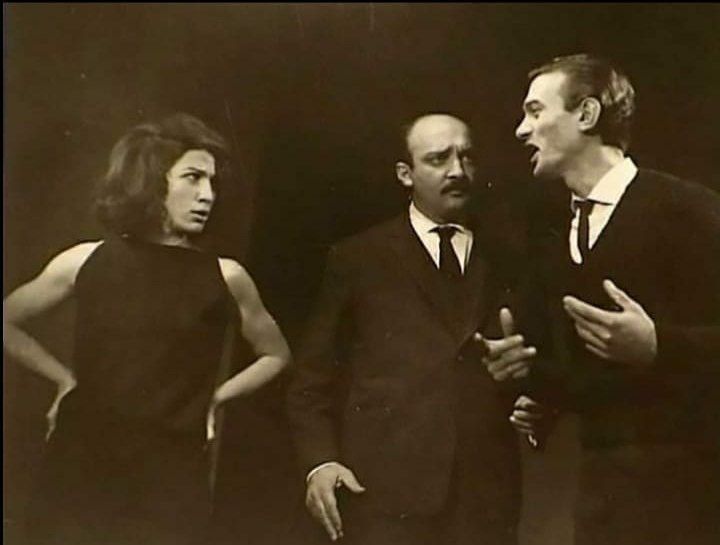

-

Forugh and Parviz Shapour

Eventually,

in 1951, after much back-and-forth, the two married. Pouran Farrokhzad

described the sixteen-year-old Forugh as "full of feeling, restless, and

crazy" who married Parviz Shapour, a "normal, logical, and calculating"

man. A year later, coinciding with the birth of their only child, Kamiar,

Forugh published her first collection of poems named "Asir" (The

Captive). It seems that from that year and that book, the differences between

the two began. The world of poetry and intellectualism that Forugh had entered

did not harmonize with the calm, family life she had.

Eventually,

in November 1955, Forugh and Parviz Shapour separated, and by law, Kamiar

stayed with Parviz. Parviz, using the child's well-being as a pretext, did not

allow Forugh to visit her son, and she never saw her son again for the rest of

her life.

Forough,

Parviz Shapour, and their son Kamiar

At

the outset of their separation, both Parviz and Forough expressed disdain and

disgust towards their marriage to each other. Forough, in a letter to Ebrahim

Golestan, regrets her marriage, writing: "That ridiculous love and

marriage at the age of sixteen destabilized the foundations of my future

life…" However, it seems that Forough always held respect and affection

for her first love. For a while after their separation, Parviz provided

financial support to Forough, and she, in turn, dedicated her collection

"The Wall" in 1956 by writing, "Dedicated to Parviz, in memory

of our shared past and with the hope that my modest gift can respond to his

boundless kindness."

According

to Emran Salahi, poet and close friend of Shapour and a childhood neighbor of

Forough: "In the letters she wrote to Parviz after their separation,

Forough is more in love than ever."

Forough's

letters to Parviz were later published by Forough’s son Kamiar and Emran Salahi

in a book titled "The First Heartbeats of My Heart." This book

includes 16 letters before marriage, 22 during their marriage, and 18 after

their separation until Forough was 21 years old. Even during Forough's trip to

Italy after their separation, they continued corresponding, and in these

letters, Forough constantly spoke of Shapour's kindness:

"…I

may not have been a good wife to you, but I hope you still accept my friendship.

Just as I still, and forever, see you as the only one I can truly trust and

share my pain with.

…I

swear to you by Kami's life, remembering the days we lived together, loved each

other, and now I regret even a moment of it—if I did wrong, forgive me. I have

changed, changed a lot. I was a child, and now life’s hardships have bewildered

me. Parviz, forget the past and write about Kami sometimes so I can at least

study here with a peaceful mind…"

Some

time after Forough's trip to Italy, Parviz stopped responding to Forough's

letters, and their communication ceased:

"Parviz,

I have written at least ten letters to you that I haven't sent. I don't know

why? I thought you no longer loved me because you didn’t reply to my letters. A

few days ago, you sent me a book, and no matter how much I flipped through it,

hoping you had written something for me, there was nothing. I am deeply

saddened; you were supposed to write to me, we were supposed to be for each

other, but you either forgot me or didn’t deem me worthy to write me back

twice, but I always remember you…"

Forough

had to choose between Shapour, family life, and poetry, and dedicated herself

to one. As she writes: "That’s the issue. If you want to be a poet,

sacrifice yourself to poetry. Skip a lot of words and accounts. Set aside many

simple and satisfying happiness’s. Build a wall around yourself and inside this

environment start being born anew, shaping, thinking, and discovering different

meanings of different concepts… That's what I'm doing - but it is bitter - very

bitter. And it requires perseverance and capacity…"

Forough,

after separating from Shapour, returned to her family for a while but could not

live with them and, with the help of her friends, rented a house and continued

to live alone. Pouran, Forough's sister, says: "When her poem 'Sin' and

her other poems were published, poets and artists of her time gathered around

her, and my father was strongly opposed to Forough's actions. He said Forough

was bringing shame to our family and eventually threw her out of the

house."

During

Forough's separation, the footnote "Blue Blossoms" by Nasser Khodayar

was published in the Roshanfekr magazine. Nasser Khodayar was a friend of

Shapour who had stayed at Forough and Shapour’s house for a week. After

returning from Ahvaz, Khodayar began publishing the story of "Blue

Blossoms" in Roshanfekr magazine, which touched on aspects of Forough

Farrokhzad’s life. Forough was so angry about the publication of this story,

which was a result of Khodayar's stay at her home, that for a long time

afterwards, she always said, "I am painfully regretful and ashamed of this

incident. In my entire life, I only feel regret about this childish and foolish

affair."

After

this incident and considering the family issues, Forough was admitted to

Rezaieh Psychiatric Hospital. Nader Naderpour commented on this event:

"One morning, Fereydoun called me and informed me that Forough was upset

and had been taken to Dr. Rezaieh's sanatorium. When I asked the reason, he

said that Forough had developed severe mental distress due to the publication

of Nasser Khodayar's 'Blue Blossoms,' which had begun in Roshanfekr two weeks

earlier. He added that despite his insistence on Khodayar to stop the

publication, he did not agree, and Forough had been in an abnormal condition

since last night and we took her to the sanatorium today. Forough was

hospitalized for about a month, treated with insulin injections, while the

story of 'Blue Blossoms' continued to be published." However, Nasser Khodayar

later claimed that he had written the mentioned footnote two months before that

visit and that attributing it to Forough was a conspiracy by her sister due to

Khodayar’s negative portrayal in front of Forough.

Trip

to Europe:

In

July 1956, after the publication of the collection "The Wall,"

Forough went to Rome and after a seven-month stay in Italy, moved to Munich to

be with her older brother, Amir Masoud. Later in her memoirs, she wrote:

"The pressure of life, the pressure of the environment, and the chains

that were tied to my hands and feet, which I tried with all my strength to

stand against, had exhausted and distressed me. I wanted to be a 'woman,' that

is, a 'human.'"

In a

letter to her father: "...now why I have come here [Munich] and why I

endure the torment of hunger, homelessness, and a thousand other miseries, is

because I love home. I didn't want to walk aimlessly in the streets from

morning to night, bearing the fatigue and mental pressure of everyone's

conversation, just because I am a stranger at home and cannot identify myself

and have peace. Now I have come here ... I am free, the freedom that you were

afraid to give me."

In

August 1957, Forough returned to Tehran and settled in a rented house. "In

the summers, all these windows, which are now closed and dark, would stay open

and lit until late at night, and whenever I pass by them at any time of the

night, I am confronted by several pairs of curious and nosy eyes that seem to

impudently and insolently ask me: 'Where have you been until now?' They want to

see who I have returned home with and who has accompanied me to my house."

Getting

to Know Ebrahim Golestan: Forugh Farrokhzad's Entrance into Cinema and

"The House is Black"

In

September 1958, Forugh Farrokhzad became acquainted with Ebrahim Golestan.

Golestan, a director, storyteller, translator, journalist, and photographer

with a unique style, played a significant role in Forugh’s intellectual

development and transformation. Sadegh Chubak has said, "In my personal

opinion… Golestan’s influence and knowledge significantly contributed to

shaping Forugh’s personality… This is merely my personal belief. This by no

means diminishes Forugh’s own worth. I witnessed Forugh being drawn to reading

and good literature through Golestan, even showing interest…"

However,

Ebrahim Golestan does not quite agree: "... I absolutely do not believe

these statements; it is unfair! ... Well, a library catalog could do the same

for a requester. If it’s just to this extent, then I accept it! ... It’s

unfair. It’s an insult to her capabilities. I have no desire to hear such

interpretations. If I were such a capable alchemist that I could turn coal into

diamond… why would I neglect myself?..."

During

her continued association with Golestan, Forugh ventured into filmmaking; she

underwent a professional apprenticeship for sound recording and equipment

repair in Europe, prepared several documentary films for Golestan Film,

participated in and helped produce a film about a marriage proposal ceremony in

Iran, produced several advertising films, and had other joint experiences with

Golestan. Finally, she directed "The House is Black," about a leper

colony in Tabriz. The film was commissioned by the "Society for Assistance

to Lepers" in autumn 1962 and produced by Ebrahim Golestan at Golestan

Film Organization.

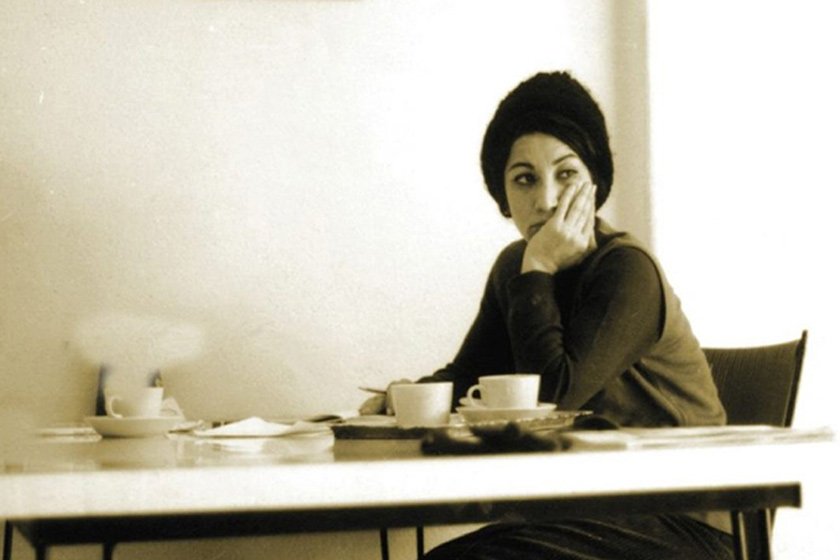

Forugh

and Filmmaking

In

an interview with Roshanfekr magazine on February 20, 1964, Forugh said about

the film: "In my view, this film is about the lives of lepers and at the

same time about life itself. It is an example of life in general. It is a

portrayal of being useless, isolated, and separate. Even healthy people outside

the leper colony might exhibit these psychological traits without having

leprosy. A young man aimlessly walking down the street is no different from the

young leper in the film continuously walking along the wall. This young man

also has pains that we are unaware of."

"The

House is Black"

"The

House is Black" won the award for Best Documentary at the Oberhausen

Festival in Italy in winter 1964. However, receiving this award was not

particularly significant to Forugh: "I was indifferent to the whole

affair. I had already taken the pleasure I should from the work. They might as

well give me a doll as a prize; what does a doll mean? A prize is just a kind

of doll. What matters is that I have confidence in my work and feel satisfied.

Now, if all the people in the world were to gather and, say, throw rotten eggs

at me, it wouldn’t matter. Without this personal assurance and satisfaction,

even if they dumped all the world’s festival awards into a tray and brought

them to me, they would be worthless."

Forugh

in an interview about entering the world of filmmaking said: "[Cinema] is

a means of expression for me. Just because I have spent a lifetime writing

poetry does not mean that poetry is the only means of expression. I like

cinema, and I would work in any other field as well. If there was no poetry, I

would act in theater. If there was no theater, I would make films. Whether I

continue depends on whether I have something to say, of course, if I have

something to say."

In

the late winter of 1963, the collection "Another Birth," comprising

35 poems from the years 1959 to 1963, was published by Morvarid Publications.

In the "Instead of a Preface" section of the book, there is a

dedication that simply states: "To E. G.," followed by a verse from

the poem "Another Birth." The collection "Another Birth"

revealed a new facet of Forough's poetry and her capabilities. The depth and

transformation in the poet's thinking in this collection are clearly

discernible; to such an extent that Mehdi Akhavan-Sales writes about it,

"I believe that 'Another Birth' was not only a rebirth for Forough but

also a fortunate birth for the vibrant and progressive contemporary Persian

poetry and a fresh rebirth for Persian poetry itself."

End Item/

Labels: TARNA POETRY ARTNEWS NEWS IRAN FEMALE POET Forough Farrokhzad DIVAR BOOK contemporary Persian poetry